Plotting the Return to a Great New Dam-Building Era

Roadway signs such as this exist along stretches of I-5 and Hwy 99 in the San Joaquin Valley.

There was excitement in the room—with good reason. The California Water Commission was getting a briefing by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) on its next California Water Plan update.

A unanimous legislature had recently passed, SB-72, a “reform” to the California Water Plan’s 5-Year Updates, beginning for the 2028 & 2033 Updates. SB-72’s marquee provision was setting a 9-million-acre-foot interim target for the Plan Update—a weird and undefined combination of new storage capacity, water, conservation, reclamation, and desalination. (See previous blog on this subject).

For the state’s water agency leaders (informally known as “water buffalos”, which is patently unfair to the real thing), the hope was for a plan to deliver 9-million acre-feet of new water each and every year. For a state that uses 42-million acre-feet annually, that’s a lot (surface storage capacity is about the same). An acre-foot is a measure of water volume—it’s one acre of water, one foot deep. Another way to visualize 9 million acre-feet of water is to imagine a football field with 6.8 million feet of water on top.

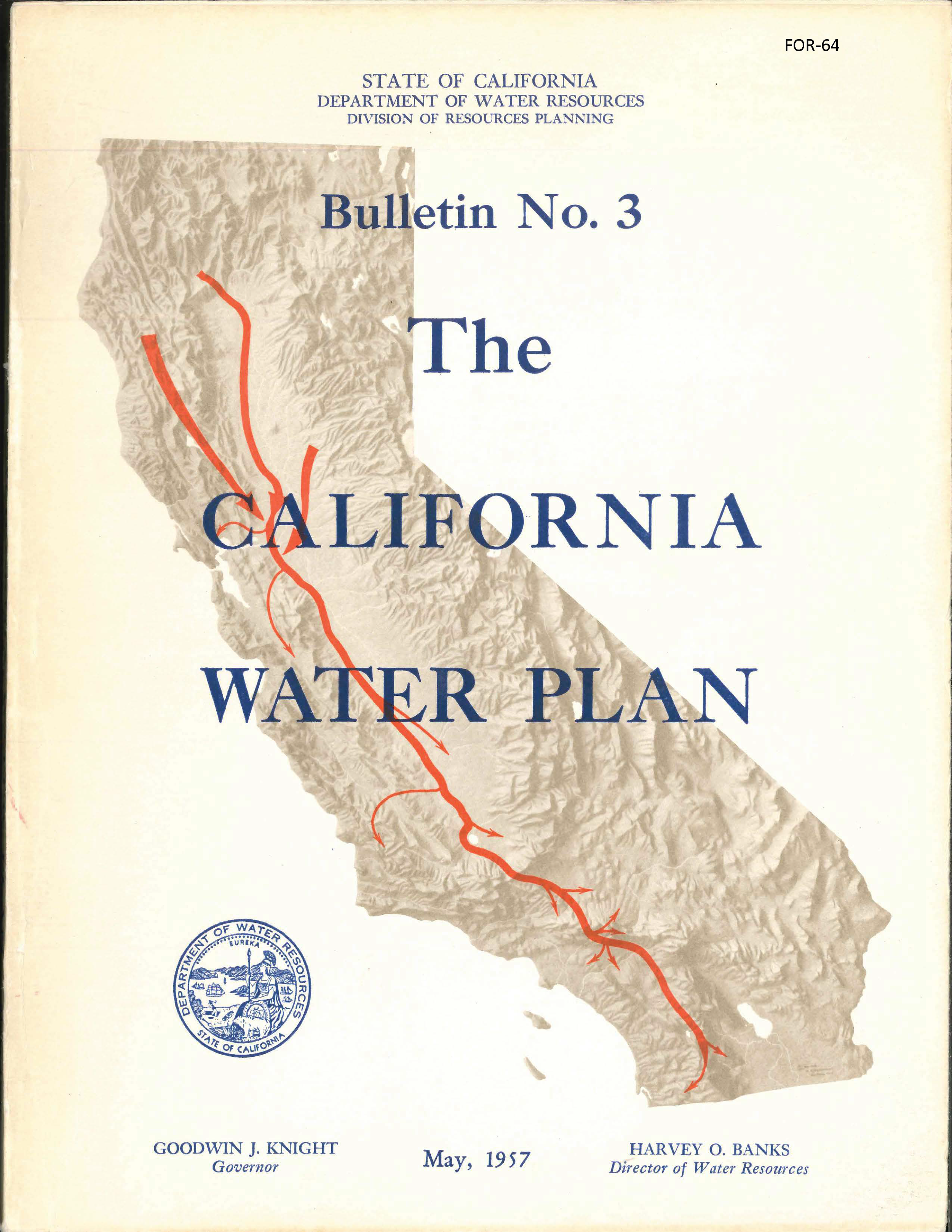

Like elephants, the water buffalos have long memories. For many of them, the only real California Water Plan was the original dam-every-river-and-stream-in-sight 1957 Bulletin #3 California Water Plan. That plan plundered the north state for a reason: an average of 18,330,000 acre-feet per year would be exported across the Delta from the north-state to the “areas of deficiency” in the south-state and San Joaquin Valley (the average export today is 4,000,000).

The cover of the infamous Bulletin No. 3, showing with clear visuals California’s intent to send all its water from the north- to south-state.

DWR’s Director Harvey O. Banks penned Bulletin #3’s introduction in confident words:

Bulletin No. 3 presents a master plan to guide and coordinate the activities of all agencies in the planning, construction, and operation of works required for the control, development, protection, conservation, distribution, and utilization of California’s water resources for the benefit of all areas of the State and for all beneficial purposes.

In other words, one plan to rule them all (and to complete the reference, “and in the darkness bind them”). Crashing against financial and environmental backlash, the hubris of the 1957 plan was soon recognized. Future updates of the plan adopted more modest goals. But once ignited, that original flame has burned in the hearts of many water agencies, including in the long lines of their general manager successors.

So, DWR’s January 2026 presentation did not disappoint the water buffalo crowd. Finally, for them, DWR was announcing its return to its roots. According to DWR’s presentation(1), the next plan:

Establishes first-ever statewide water supply target — an interim target of 9 million acre-feet by 2040

Provides actionable direction — moves the Water Plan from advisory guidance to a clear implementation framework

Expands coordination and consultation — planning reflects statewide priorities and regional realities

The State Water Project Contractors, a group of many key water districts that purchase water from the state, and the San Joaquin Valley Water Blueprint crowd, the latter, touting their “unified plan” to bring millions of acre-feet to the east side of the Valley, all pledged their assistance and fealty to their expected vision of the Water Plan Updates.

Of course, scratching together 9-million acre-feet of water is not going to be easy. For something like that, the original Bulletin #3 planned to convert California’s north coast rivers into gigantic holding tanks that would pour into tunnels piercing the northern Coast Ranges for delivery to the Sacramento River and across the Delta.

Eel River, FOR Archives, 2012.

Given the expense and overlapping state and national wild & scenic river designations of the north coast rivers, some might lobby the state to invade Oregon and tap the Columbia River — perhaps calling it the “Presidential Plan.”

Building storage dams is easier. No invasions needed. Just find a few dozen out-of-the-way canyons, and start moving dirt. Storage dams don’t even have to produce much (or any) water, but they do make water buffalos happy and can meet the vague Water Plan Update target as well, although it wouldn’t exactly be very smart.

But the state has other choices. The Water Plan Update could undertake the hard but necessary work to plan for the infrastructure and institutions the state will need in the future as it right sizes its water use to work with the water reasonably available and build more local self-reliance —and to give its rivers more life too. The intellectual brainpower to do that exists. Whether the political will exists is another matter.

Resources